Readers’ Language READER-CENTERED WRITING

Use the Reader’s Language & Concepts

When you want someone to do something, you should make it as easy as possible for them to understand and comply. This means figuring out what “language” the audience understands and what concepts are familiar and easy for them to use.

Using the audience’s language & concepts means communicating in a “language” the audience understands and using concepts that are meaningful and familiar to them.

Quick Example

|

images via Fifth in the Middle

|

Depending on where you grew up and how your earliest teachers explained things to do, there’s a good chance that holding or folding a sheet of 8.5″ x 11″ standard sized paper hamburger style or hotdog style means something to you.

Dammit. While I was trying to come up with real-world examples to help explain this concept, I thought thinking through audience + language using “hamburger and hotdog style” folding was really brilliant… or at least original. Apparently, it is not. See this short post “Know Your Audience” from Parthenon Publishing.

Anyway… why hamburger and hotdog instead of vertical and horizontal? Because very young children don’t know the words “vertical” and “horizontal”; or perhaps they know the words and what they mean, but can’t quickly recall which is which; or perhaps they know the terms but have trouble applying them to material reality (the paper on the desk in front of them).

For young children, hamburger and hotdog are easy to conceptualize or imagine. Vertical and horizontal are not. So, if you really want a bunch of five year olds to fold a sheet of 8.5″ x 11″ paper in a particular way, then you need to use the language/concepts they understand—hamburger and hotdog.

Rhetorical Situation & Broad Considerations

To figure out the audience’s preferred language and concepts most familiar to them, you should revisit your consideration of audience in the rhetorical situation. While any and/or all of the “audience” prompts (included below) may be relevant, pay special attention to

the audience’s background and knowledge

- what is their demographic background? experience? education? level of expertise? familiarity?

- what are their job functions/responsibilities? what personal/family roles do they occupy?

the context in which your audience will read/use your document

- why is the audience reading the document? what do they need from it?

- where are how will your reader use your document?

- what is the their physical environment? time of day? mental state? are they alone or with others?

- on what medium are they reading your document? on paper? on a computer or tablet screen? on a smart phone?

other audience considerations

- what is their preferred/most familiar diction (choice of words/language, including the level, style, definitions, explanations)?

- What sort of genre, design, layout, organization might be best for them?

- Would they appreciate the use of any visuals, graphics, illustrations, lists, etc?

Example: Directions Dialogue

I’m so bad with cardinal directions that I actually tried making all of the norths, souths, easts, and wests match up with the lefts and rights… but I couldn’t do it. So I sorta fudged the accuracy of the directions, but hopefully, you still get my point.

I don’t do cardinal directions—I just can’t. I don’t know my north from south, or east from west. Telling me something is at the northwest corner of whatever-the-heck is absolutely meaningless to me. I don’t do miles, either… unless I’m staring at the odometer (and when I stare at the odometer, my husband’s “about X miles” is never accurate).

Every time I’ve ever been lost and stopped at a gas station to ask for directions2 I still use a LG enV2 (VX9100) dumb phone that came out in 2008. Obviously, it does not have GPS., I’ve listened to the attendant list all the norths, and wests, and miles. I’ve nodded along, said “thank you so much” in my most polite voice, walked out and felt stupid because I had no idea what the attendant meant, and even if I did, I couldn’t remember any of it as soon as I was back in my car.

I have no sense of direction, no spatial awareness, and my memory is terrible for stuff like that.If I’m being honest, when I’m stressed or anxious (like when I’m late for an appointment, lost, and don’t know where I’m going) even my quick recall of left and right is a little shaky.

If you’re giving me directions, and you genuinely care about me getting to where-ever I’m going, then you’ll give me directions in lefts and rights, in minutes, and in landmarks I’m likely to recognize… and you’ll write it all down (because if you know me—really know me—you know that I’ll listen and nod along, but have no memory of anything as soon as you’re done talking).

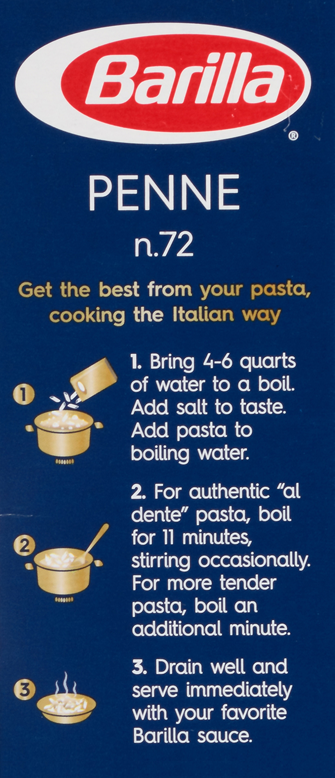

Example: Boiling Pasta? Salt the Water.

What sized pot? My medium pot, the big pot, or the really big pot? (I have no idea how much any of my pots hold). 4-6 quarts… ummm… I can estimate cups, and maybe gallons, but not quarts. I mean, I think quarts are close to liters, and I can picture a 2 liter bottle…? So, if a quart is close to a liter, then I should boil 1 box of pasta in 2-3 two liter bottles worth of water. I think.

And salt to taste… in the water. Salt the water until it tastes… good? To what taste? My preference? I don’t drink salt water, so I don’t know what “to taste” means.

Chefs on TV just dump salt in before boiling water for pasta. I dunno, a couple of tablespoons? But that seems like a lot.

Not that it’s a huge deal, but for the longest time, I had no idea how much salt to add to the water before boiling pasta (nor how much water to use, nor what sized pot).

Until some TV chef said… pasta water should taste like sea water.

Got it. I’ve accidentally ingested enough ocean water in my life to know—without a doubt—how salty sea water is.

That? That makes sense to me.

Because that TV chef put the “measurement” into a concept I knew and understood, I finally understood the instruction. It was finally a meaningful, usable concept to me.

Audience Prompts

To determine concepts and language the audience understands and is familiar/comfortable with, you may have to go back and think through your rhetorical situation—specifically, the audience. The prompts are copied below.

Analyzing Rhetorical Situation: Audience Prompts

|

Identification:

Background:

Value/s:

Knowledge/s:

Expectations:

|

Context:

Potentials:

Adaptations:

|

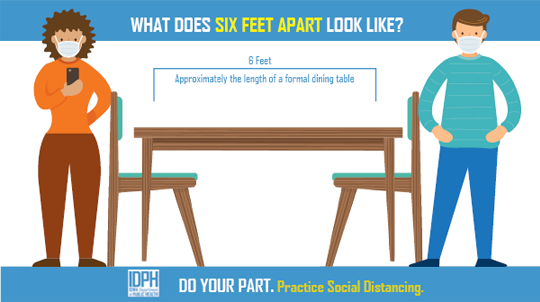

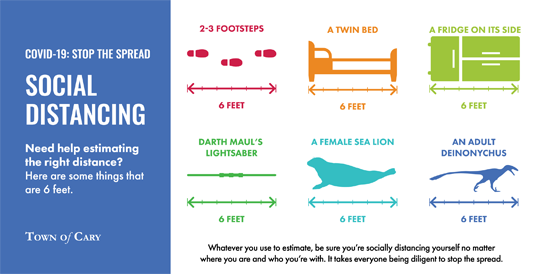

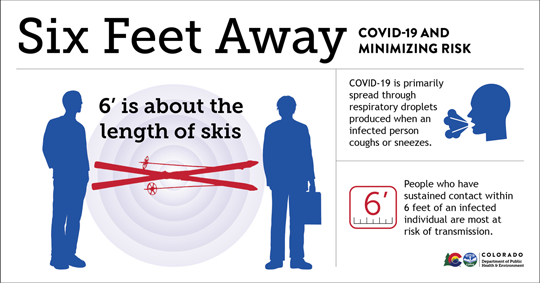

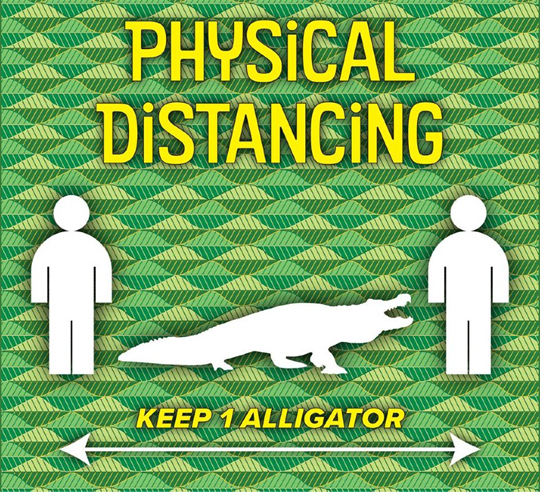

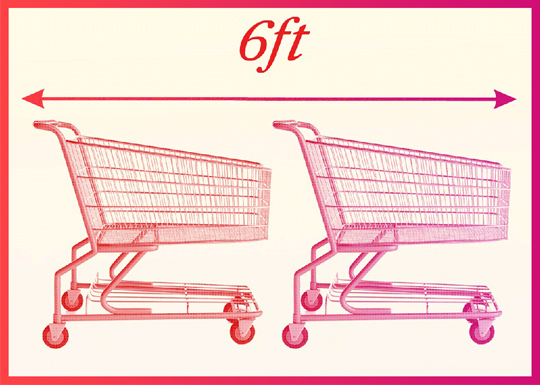

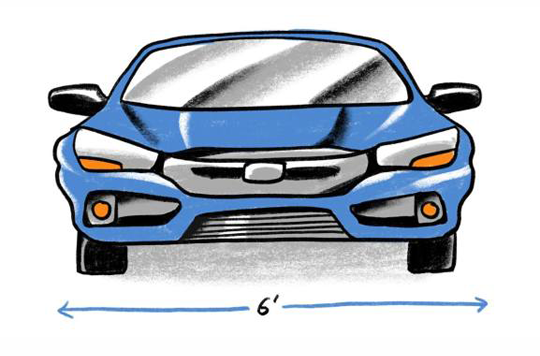

Example: Social Distancing, 6 Feet(?) Apart

Hopefully, you have much better visuo-spatial intelligence than I do. But if you’re like me, you can’t immediately or mentally estimate distances.

In a pandemic situation—when remembering that keeping 6 feet between you and someone else—is potentially critically important to people’s health and safety, it’s a good idea to keep reminding everyone with frequent messages, signs, and stickers.

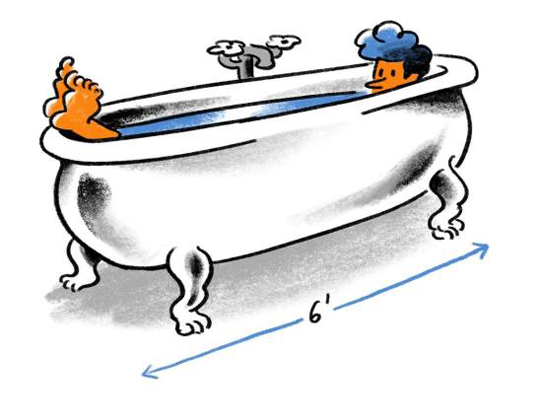

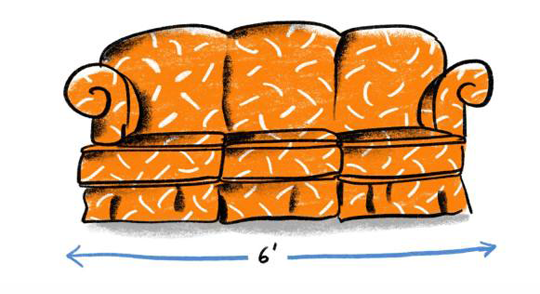

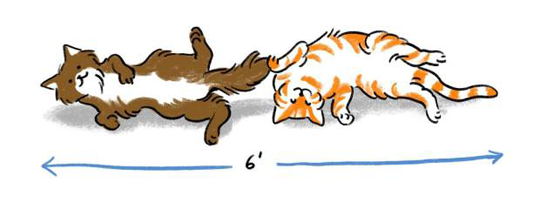

And, in a pandemic situation—when understanding what it means to keep 6 feet between you and someone else—is equally important to health and safety, it’s also a good idea to help people visualize and understand what “6 feet” really means. (6 feet, or 2 meters, or one dolphin, or an alligator, or 8 large pizzas…. )

Some of these are better (for me) than others. Frankly, I don’t think the dining table visualizations are helpful (like the “formal dining table” image in the first column, second image down) because everyone has differently sized tables.

Not excited about the bathtub (first column, third down), either. Most people can sit down in a residental bathtub, but can’t lay down… (and even laying down, most of us arent 6 foot long/tall). For science, I just measured the bottom of our bathtub and it’s just about 4 feet. So, yeah, the bathtub visualization isn’t great.

|

Nina Keck for VPR

IDPH – Public Health, via Twitter

Max Pepper for CNN, via Mercury News

Max Pepper for CNN, via Mercury News

Max Pepper for CNN, via Mercury News

|

Max Pepper for CNN, via Mercury News

Matt Turner for NPS, via Washingtonian

WA Dept. of Health, via Medium

Town of Cary, via Twitter

Max Pepper for CNN, via Mercury News

Dimensions Guide, via ABC 7 News

CO Dept. of Public Health, via Twitter

|

Leon County, via Facebook

Max Pepper for CNN, via Mercury News

Brenna Hernandez for Shedd Aqaurium, via ABC7

via WRCBTV

Max Pepper for CNN, via Mercury News

|