Research Integration, Citation, & Documentation

Goals for Professional Attribution

| ethicality | clarity | consistency | transparency |

|

readability

write and format your text, citations, and documentation in a way that’s least intrusive to the text

|

usability

write and format your text, citations, and documentation so readers to find the sources themselves

|

||

Most research is problematic.

It can be intentionally or unintentionally biased. It can come from an interested source with stakes in the information. It can be incomplete. It can fail to be representative of some larger group. It can be specific to a time, location, type, or some other subset. It can be presented in dissimilar, incomparable, or unequal units.

When research is problematic, the problem should be made clear to your reader. Problems of bias, sourcing, representation, completeness, limitation, and measurement should be faithfully communicated to the reader rather than hidden or otherwise obscured.

In research and writing, we use “credibility” to mean whether or not something is accurate, whether or not it can be believed or trusted—but that’s an incomplete picture of what credibility is. Credibility can rarely be assessed in binary oppositions—it’s rarely either accurate or inaccurate, correct or incorrect, credible or unsound, truthful or dishonest. Usually, it’s somewhere in the middle. While we should aim for the credible, accurate, and truthful side of the spectrum, research that falls short shouldn’t be discounted. Instead, it should be evaluated for what it is and explained or noted in context.

For our purposes (and many professional purposes), credibility is trustworthiness in a particular context. Being credible means representing research as what it is, which demands understanding the rhetorical situation and representing that rhetorical situation in good faith.

Above all else, be ethical about where your information comes from.

Additionally,

- If your information comes from a “biased” source, be clear about that bias.

- If your information incomplete, limited, or dissimilar, be clear about those problems.

- In situations where you have to evaluate, combine, and/or quantify incomparable, unparallel, incomplete, or inexact “data,” just be forthcoming and clear about what you’re doing and how you’re doing it.

Citation & Documentation in the Workplace

…ask your employer how he or she wants information to be documented. Sometimes, in the world of work, employers prefer all information to be documented in footnotes or cited parenthetically in the text.

Ordinarily you won’t need to use the complex system required for documentation in college research papers. However, you will still need to identify the sources of quotations, facts, and someone else’s original ideas. Crediting outside sources is more than a matter of honesty; it also:

- Lends authority to your assertions

- Demonstrates your thoroughness and knowledge

- Allows your reader to pursue the subject further

In many careers (nonacademic, not research focused), you will not be expected to conform to any particular citation/documentation style (such as MLA, APA, AP, Chigago, etc.). But, that doesn’t mean citation and documentation are unimportant! You must (MUST) give credit (or blame) to the sources from which you gathered your information.

If your company or organization uses a particular style guide, then you’ll need to use that guide. If not, instead of adhering to a particular style guide, aim for ethicality, clarity, consistency, transparency, readability, and usability.

Definitions

| attribution |

giving credit to original sources

Attribution is a generic umbrella term for the general practice of giving credit to sources, and the methods for giving credit to sources (in the text and/or in a list of references)

|

| citation |

acknowledgment of a source in the body of a text or within a graphic representation of data

Citation can be included in the text of a sentence, in parentheses within or after text or data, or with superscript notations (usually numbers) that refer to footnotes or endnotes.

|

| documentation |

providing bibliographic information that allows a reader to locate your source and specific text or data used

Documentation is often provided in a bibliography, works cited, or list of references (depending on style) at the end of the text or included as a section of a multi-part text.

|

| references |

individual entries in bibliography, works cited, or list of references

Entries should be parallel (to each other) in structure and provide enough information to give credit and allow readers to find the specific source material used.

|

What Needs Attribution? (Citation and Documentation)

- quotation; when you reproduce a phrase, sentence, or sentences from a source word for word; you must indicate a direct quotation with quotation marks

- paraphrase; when you put an idea or passage from a source into your own words; paraphrase is usually more concise than in the original

- summary; when you put a source’s main idea(s) into your own words, including only the main point(s)

- facts or statistics; when you include facts or statistics (numerical or otherwise) gathered from a source

What Does Not Need to Be Cited?: You do not need to cite your sources if you are writing your own words, ideas, or original research. You do not need to cite information that is considered common knowledge, such as facts found in many sources (e.g., George Washington became the nation’s first president in 1789), or easily observable phenomenon (e.g., most college students use smart phones).

When in Doubt: When you’re not sure about whether to cite something, err on the side of caution. It’s always better to over-cite or unnecessarily cite than to risk being unethical (and risk plagiarism).

Read “When to Cite Sources” and “Not-So-Common Knowledge” from “Academic Integrity at Princeton.”

Quotation, Paraphrase, Summary

| QUOTATION | |

|

when to

quote

|

When you’re going to discuss the author’s choice of words; when the wording is particularly memorable, vivid, or interesting; when you cannot paraphrase or summarize.

|

|

how to

quote

|

Quotations must be identical to the original, using a narrow segment of the source. They must match the source document word for word and must be attributed to the original author.*

|

| PARAPHRASE | |

|

when to

paraphrase

|

When you want to use the details but the original language itself is not particularly striking or important to the point you want to make.

|

|

how to

paraphrase

|

Paraphrasing involves putting a passage from source material into your own words, usually condensing it. Paraphrase must also be attributed to the original source.*

|

| SUMMARY | |

|

when to

summarize

|

When you want to discuss the source as a whole, distilling its main idea, central point(s), or main focus(es).

|

|

how to

summarize

|

Summarizing involves putting the main idea(s) into your own words, including only the main point(s) or broadly describing the argument. Summarized ideas must be attributed to the original source.*

|

Parenthetical Citation vs. Natural Language Citation

More Examples of Parenthetical and Natural Language Citations

Using Footnotes

Using footnotes as citation can replace parenthetical or natural language citations in the body of your text.* Depending on the formality, purpose, and audience of the document, footnotes can be preferable because they’re the least intrusive form of citation. In other words, instead of interrupting ideas, sentences, or the “flow” of the text with a parenthetical citation, a footnote allows the least disruption to the text.

According to the Purdue Online Writing Lab, when using footnotes: “insert a number formatted in superscript following almost any punctuation mark. Footnote numbers should not follow dashes ( — ), and if they appear in a sentence in parentheses, the footnote number should be inserted within the parentheses.”

Above all else, aim for ethical, transparent citation and documentation (even if that requires you to put a superscript number in the middle of a sentence).

“Footnotes” according to Rules of Thumb for Business Writers

You can use footnotes either for detailed identification of a source or for supplementary information. Footnotes are the least intrusive method of referring to sources, and word-processing programs make the formatting relatively easy.

You may use a footnote at the end of your report to refer to a single source you have used throughout. For multiple sources or for specific page identification of quotations or illustrations, use a series of footnotes (at the bottom of each page requiring a source identification) or endnotes (in a separate section at the end, labeled Endnotes, in regular font, without quotation marks). With footnotes or endnotes, begin with the number 1 and use a new number each time you cite a source. For each subsequent use of the same source, use the author’s last name and the page number.

To identify a source, include:

- Author (first name first)—if no author is listed, put the organization that created the document.

- Title (for an article, include the title of the article, in quotation marks, and the title of the publication, italicized).

- Additional information, depending on the type of source.

An Example

List of References (& Bibliographies, Works Cited, and Works Consulted)

What’s the Difference?

How the list of sources/works is titled depends on a few factors:

- the style manual the author is using/following (if any),

- The type, length, and/or genre of the text, and

- whether the sources are cited in the author’s text or simply “consulted.”

MLA: The MLA uses parenthetical author-page number for in n-text citations. Although past editions have slightly different recommendations, the 8th edition of the MLA Handbook recommends only a list of “Works Cited” that includes works that are drawn from (and cited) in the body of the text, listed alphabetically by author’s last name (or first available information). [ What is the difference…? ]

Chicago: The Chicago Manual of Style recommends a “Bibliography” that includes both works cited and works consulted, listed alphabetically by author’s last name (or first available information). [ 14.62: Format and Placement of Bibliography ]

IEEE: The IEEE uses numerals in square brackets for in-text citations. At the end of the text, the “List of References” or “Reference List” should be list sources and bibliographic information sequentially (using the same numeral as the citation)—not alphabetically. [ List of References ]

APA: The APA uses parenthetical author-date for in-text citations, and suggests “References” at the end of the text with each entry listed in alphabetical order. [ Purdue Owl: APA Style ]

“List of References Consulted” according to Rules of Thumb for Business Writers

Using in-text references or footnotes should be sufficient to acknowledge sources in most business writing. However, on occasion, you may need or want to provide a list—labeled “Bibliography,” “References,” “Recommended Reading,” “Works Cited,” or “Works Consulted”—at the end of a report. Depending on how you label it, this list can be used to acknowledge background research or the sources you have cited, or to give suggestions for further reading on the topic.

Use the same format as for footnotes. Do not number the list. Instead, put authors’ last names first and make one alphabetical list. For each entry, indent the second and additional lines.

Note: This chapter presents a simplified version of the documentation styles recommended by the American Psychological Association, the Chicago Manual of Style, the Council of Biology Editors, and the Modern Language Association.

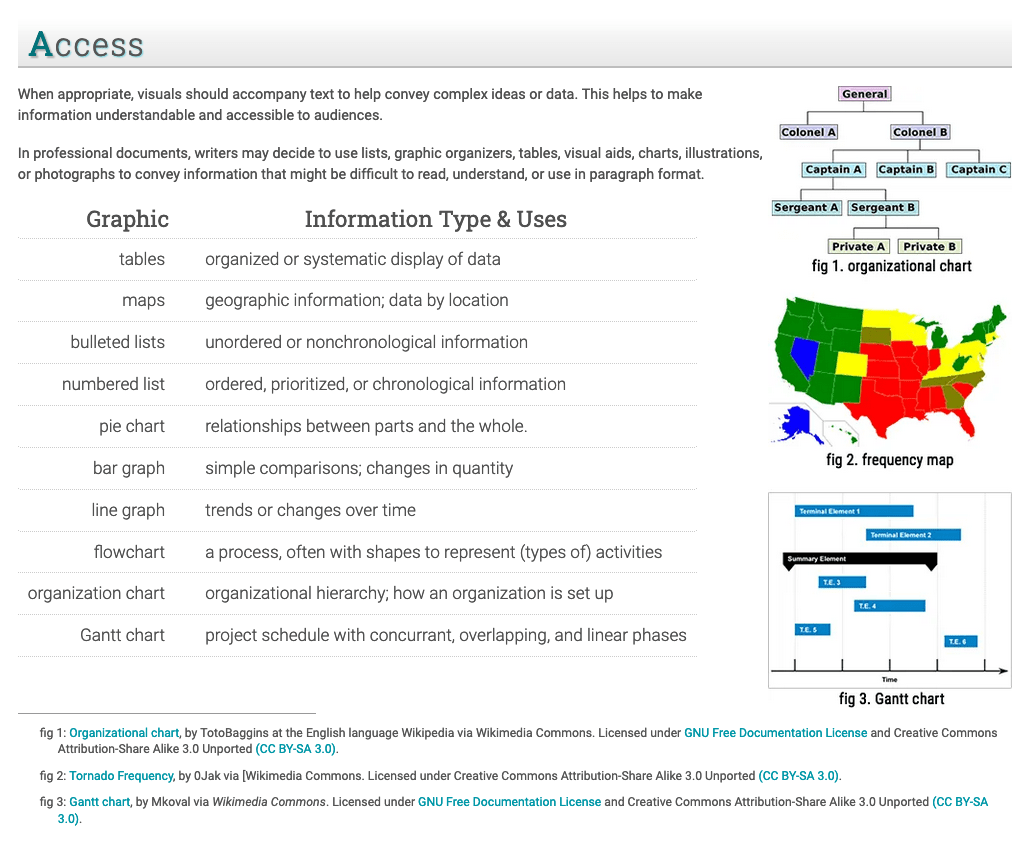

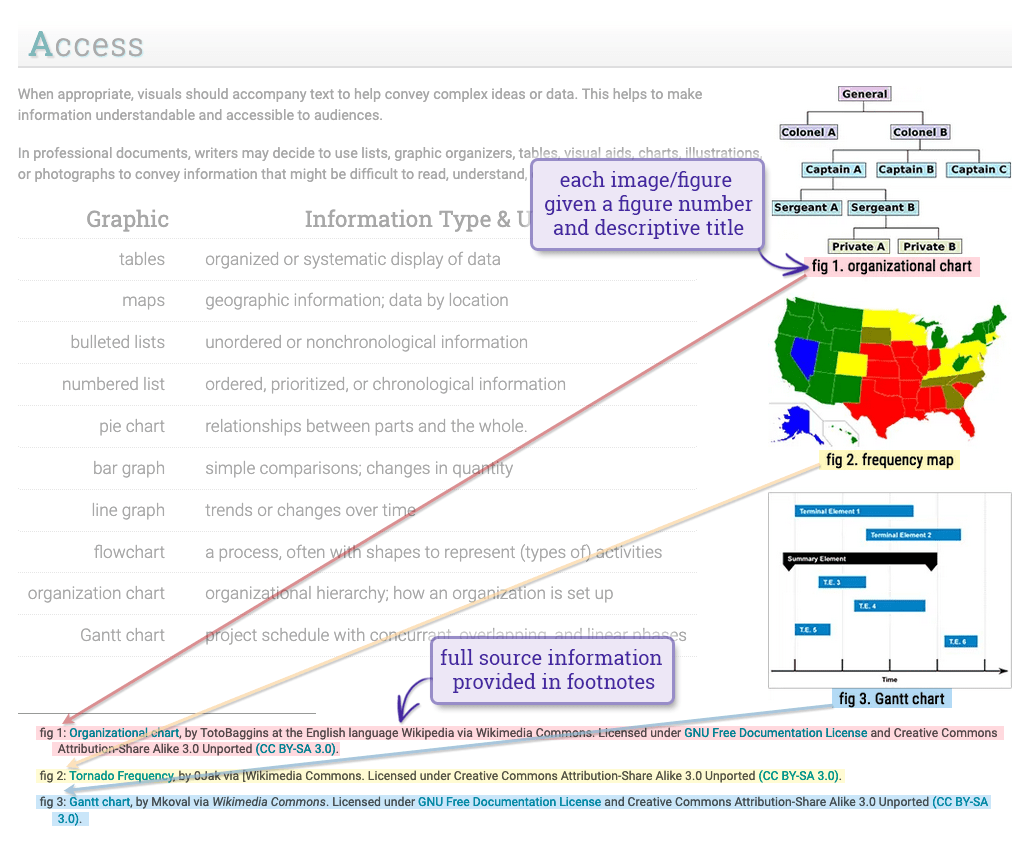

Image Attribution (Citation & Documentation)

A form of protection provided by the laws of the United States for “original works of authorship”, including literary, dramatic, musical, architectural, cartographic, choreographic, pantomimic, pictorial, graphic, sculptural, and audiovisual creations.

Copyright is a form of protection grounded in the U.S. Constitution and granted by law for original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Copyright covers both published and unpublished works.

Copyright, a form of intellectual property law, protects original works of authorship including literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, such as poetry, novels, movies, songs, computer software, and architecture. Copyright does not protect facts, ideas, systems, or methods of operation, although it may protect the way these things are expressed.

Your work is under copyright protection the moment it is created and fixed in a tangible form that it is perceptible either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.

Fair use is a legal doctrine that permits limited use of copyrighted material without acquiring permission from the rights holders. It is one type of limitation and exception to the exclusive rights copyright law grants to the author of a creative work. Examples of fair use in United States copyright law include commentary, search engines, criticism, parody, news reporting, research, teaching, library archiving and scholarship. It provides for the legal, unlicensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test.

Whether use is commercial or for nonprofit educational purposes; To justify fair use, must demonstrate how use either advances knowledge or the arts through the addition of something new, analysis, criticism, etc.

Considerations include factors such as the purpose (e.g. information or entertainment), genre (e.g. unpublished novel, personal correspondence, or film), and probable audience (e.g. wide readership or private audience).

Considerations include the quantity, “quality,” and importance of the portion of the work to the whole.

When fair use is in question, a copyright owner must demonstrate negative impact on the potential market for the work.

An Example