Professional Emails

Overview

Because email is convenient and (often) immediate, writing emails may feel less formal than writing in traditional paper-based genres of communication such as letters or memos. While emails can be less formal, the principles of good professional writing still apply, and that means approaching email rhetorically. To varying degrees, the purpose and audience of your communication situation should dictate 1) whether email is an appropriate genre, and if so, 2) the content, writing style, and level of formality it requires.

Emails can be sent internally (intra-office, meaning between members of the same organization) or externally (to clients or members of other organizations). Emails may be appropriate for communications with familiar audiences and unknown audiences with whom you have not yet made contact or do not know well.

In general, email should not be used for sending sensitive or official information, or otherwise highly formal messages.

Do Emails Really Matter?

We often write and send emails without thinking much about them. But, we should think about them—rhetorically.

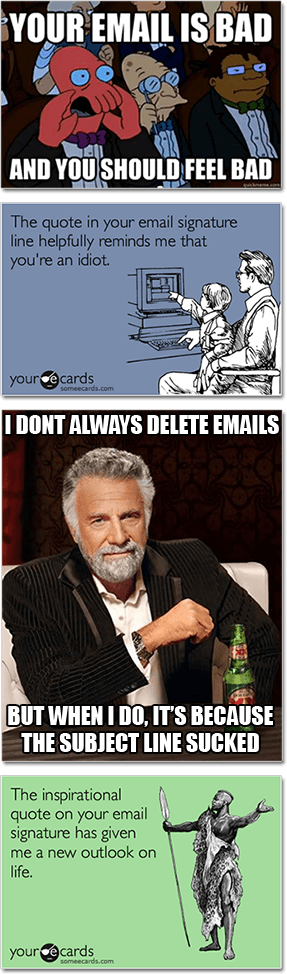

Without approaching emails rhetorically and editing carefully, we run the risk of failure—failure to appeal to audiences and maintain goodwill, failure to establish credibility and professional ethos, and failure to communicate clearly and concisely enough to achieve our purpose.

Emails are incredibly important, not just for the communication of information, but because they contribute to your ethos—the way others perceive your character, intelligence, and professionalism.

Besides that, emails also reflect the professionalism of the business or organization you represent. While any one individual may not care about how others perceive them, the business that person represents absolutely cares about how current and potential clients view them.

For those reasons, used correctly, emails are an invaluable tool for building and maintaining professional relationships.

Characteristics of Successful Emails

- employ effective subject lines (more on effective subject lines here)

- establish goodwill with greetings/salutations and complimentary closings (more on greetings, salutations, and closings here)

- limit scope to a single topic (in most, but not all, situations)

- are clear, concise, and correct, and written with a polite tone and conversational style

- use liberal paragraph breaks, graphic highlighting, headings/subheadings, and other formatting elements to facilitate reading

Email “Do” and “Don’t” List

- use lots of paragraph breaks (there is no minimum length for paragraphs—in professional writing, sometimes a paragraph can be just one sentence)

- revise for clarity, conciseness, and correctness

- proofread and edit for spelling and grammar errors

- check your tone

- use a good, informative subject line

- check for a response

- write in all caps

- use backgrounds, uncommon fonts, or images (unless images are needed)

- forget that your reader is a human being (not a machine)

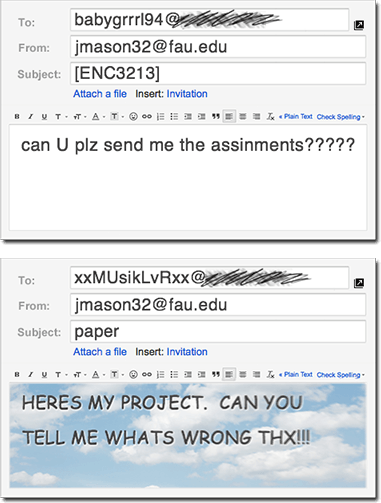

- use abbreviations, text-speak, slang, or obscenities

- write from an inappropriate email address (email addresses that reveal your age, interests, personal qualities, preferences, or characteristics are not appropriate for business correspondence)

- include unprofessional email signatures (such as quotations, scriptures, lyrics, etc.) unless they are strategic, appeal to the audience, and/or help you to acheive your purpose

Email Tone:

Please browse the following links.

Five Ways To Keep Your Tone In Check When Writing Business Emails, from The Huffington Post

Tone in Business Writing, from Purdue’s Online Writing Lab (OWL)

IBM’s Watson May Now Be Able to Tell How Snarky Your Email Is With Its New Tone Analzyer, from Digital Trends. According to Watson’s developers at IBM, the Tone Analyzer “[h]elps users understand the attitudes toward subject and audience that are implied in input text” and “understand the linguistic tones of their writing. The service uses linguistic analysis to detect and interpret emotional, social, and writing cues that are located within the text. The service also offers rhetorical suggestions for an author to improve the intended tone of their message.” [emphasis added]

Try the Tone Analyzer demo (no longer available), which “analyzes and displays the Emotion, Social, and Writing tone results” of whatever text you input. After analysis, when users click on “a highlighted word, a call to the synonym API displays suggested synonyms that either soften or strengthen the tone of that word. It also allows you to select a synonym to replace the original word, changing the tone of the message.”

A digital, rhetorical approach… how cool is that?

Additional Email Etiquette Guidelines

Read Professor Dennis Jerz’s “Top 10 Strategies for Writing Effective Email.” In particular, pay attention to numbers 1, 3, 4, and 9, which I discuss and extend below.

#1: Write a meaningful subject line. Jerz urges, “write a subject line that accurately describes the content, giving your reader a concrete reason to open your message.” If your reader doesn’t immediately know what your emails about (what you are asking about/for), there is less of a chance they will open it immediately form make a mental note to respond later. Since many professionals get tens or even hundreds of emails a day, and unclear subject line increases the chance your email will get lost behind other emails.

#3: Avoid attachments. While what Jerz says is often true, just be sure to let the situation (particularly the purpose and audience) guide your choices about whether to include a document as an attachment or include all or part of the document’s text in the body of an email. Additionally, if you do attach a file, the body of your email should indicate what it is, why you’re sending it, and what (if anything) you want the reader to do with it.

#4: Identify yourself clearly. While you may know the name, title, and/or position of the person you’re writing to, your audience may not immediately know who you are or what your relationship is to them. In situations where your reader may not know or recognize you, be sure to identify yourself in one of two ways:

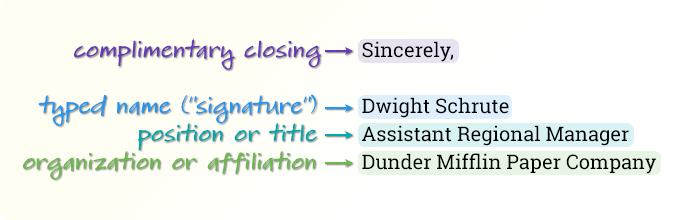

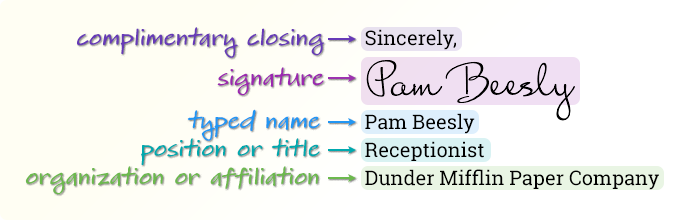

- Writing in a professional/official capacity: If you’re writing in your official role or professional capacity as a representative of an organization, you should indicate your role and affiliation after your “signature” or in the signature block.

- Writing in a personal, non-professional, or unofficial capacity: If you’re not writing on behalf of your organization or if your “role” isn’t professional, then you may identify yourself at the beginning of your correspondence.

For example, let’s say I need to email my son’s middle school principal—Principal Smith—about volunteering for their class field trip. Because the Principal Smith deals with hundreds of students and because my son has had little contact with her, I don’t assume Principal Smith would immediately know my son by name, nor would she know from my name or email address that I am a parent of one of her school’s students. For that reason, I would include my son’s name, grade, and teacher at the very beginning of the message. This information would establish context through which the principal could read the rest of the message.

#9: Respond promptly. This is great advice for both parties in an email exchange (depending on the purpose and audience, of course). If you email a request for something and your reader responds, be sure to follow up with a “thank you” and/or confirmation. This is particularly true in situations where you’re asking for something that requires the audience to respond in detail or otherwise put forth effort to respond to your request. Sometimes, your reader may respond to you with questions of her or his own, perhaps needing additional information, in order to facilitate responding to your initial request.

With quick requests that don’t require the audience a lot of time or effort, there are varying opinions about whether or not you need to respond with a thank you or confirmation. For example, let’s say you email a coworker (with whom you have a friendly, established working relationship) to ask whether the company meeting is on Monday or Tuesday. When your coworker responds with “Tthe meeting is Tuesday,” you probably don’t need to write “Thank you.” However, in most situations it doesn’t hurt to let the other party know that you received the information and that you appreciated their response.

Signature Block

If you’re writing as a representative of—or on behalf of—a business, organization, club, or other group, you can (and probably should) include your role or title and the name of your organization on separate lines after your name.

| email signature block | letter signature block |

|

|

Avoid Redundancy

It’s almost always redundant to begin professional correspondence with “My name is…” or “I’m the [ role/title ] at [ organization ]…”

There’s no need to introduce yourself—your name, role, or organization at the beginning of your correspondence because that information (your name, role or title, and organization) should go in the signature block of letters and emails or in the heading of memos.