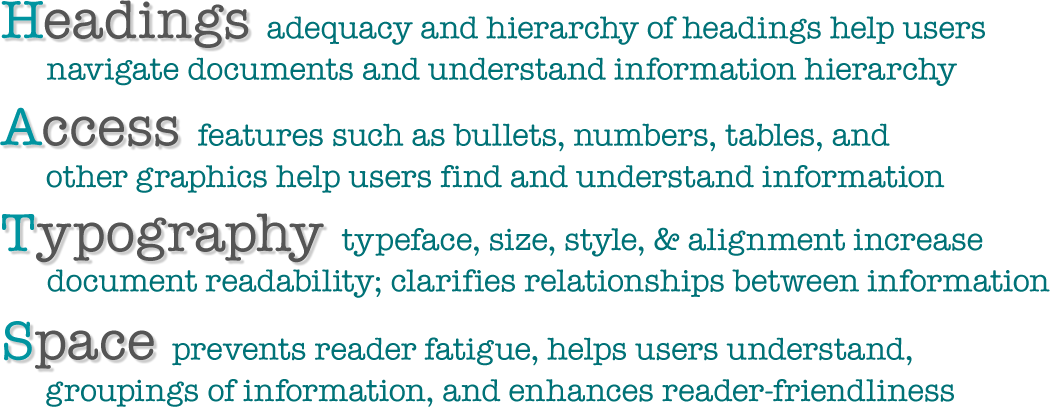

HATS: Design for Professional/Technical DocumentsHEADINGS ▪ ACCESS ▪ TYPOGRAPHY ▪ SPACE

Overview

One of the most common mistaken notions novice professional writers hold is the idea that readers will approach their writing chronologically, reading the entire document from beginning to end.

In professional arenas, audiences are comprised of different readers, different needs, and different approaches to reading. Upper management may read documents for conclusions and recommendations, accountants may read documents for the budget sections, and lawyers may read documents for the backgrounds and methods. Because professional contexts have various audiences with various needs and interests, professional writers must create documents that are easy to navigate, easy to understand, and serve the needs of all potential audiences. These documents are sometimes known as “modular documents.”

Professional writers can use “HATS” to create modular documents that are easy to navigate, access, and understand. While we’re familiar with making documents rhetorically effective, HATS is a set of considerations for making documents visually effective.

Headings

Headings are standard features of technical documents that serve several important functions:

- Provide organizational overview of the document

- Show logical development of ideas

- Show hierarchical relationship of ideas (headings, sub-headings)

- Allow the reader to scan and read selectively

- Increase readability of the document by providing breaks and white space.

Clear and specific headings (and other kinds of visual/written guides) are important for the busy reader who will scan the report to determine its overall argument or findings, or to find specific sections of interest. The report should be written in a way that allows the reader to start reading in any major section and follow the line of thought.

Headings are navigation signposts that guide readers through documents, to parts of documents, and preview forthcoming information. Headings should be adequate in number/frequency to serve as landmarks of current and forthcoming content. They should be organized hierarchically, using typeface, size, style, and alignment to show different levels of importance, specificity, and relationships.

Topic (Functional) vs. Talking (Explanatory) Headings

There are two main types of headings: Topic (or Functional) Headings and Talking (or Explanatory) Headings.

Topic (functional) headings use terms that describe the function of sections rather than the content of sections. Topic (functional) headings are often terms like “Introduction,” “Background,” “Materials,” “Methodology,” “Results,” “Discussion,” etc. In general, use function headings only in documents—such as lab reports—that have consistent structures.

More reports in professional settings are not “so strictly organized or predictable. Readers will find it much more helpful if headings concretely describe the content of each section rather than the function (TWE, 3.2 “Headings”).

The most effective talking (or explanatory, or content) “headings use concrete, descriptive language to tell the reader what to expect from the content of each section” (TWE, 3.2 “Headings”).

| Topic Headings (Generic or Functional) |

Talking Headings (Explanatory or Content) |

| Intro | The Question of Health Care for Part-Time Employees |

| Background | Social Media Strategy: Brief History of an Emerging Field |

| Qualifications | What Sports Journalists Need to Succeed |

| Methods | Identification and Selection of Florida Water Samples |

| Conclusions | The Palm Beach Parks Project: Steps to Save the Parks and Lose the Litter |

More on Writing & Organizing Headings

| “Hierarchical Headings” from Typography for Lawyers; provides a great explanation of why writers should use a tiered number system instead of traditional Roman numerals or numbered/lettered hierarchies. | Headings: Make Your Text Scannable, from David McMurray of Online Technical Writing | “Managing Headings in Print and Online Documents” from David K. Farkas from the Department of Technical Communication in the College of Engineering at University of Washington. |

| Headings, by Ginny Redish for PlainLanguage.gov | ||

| “Lesson 6: Using Parallel Form” from Professional Writing Style by Dr. Russel Hirst, Associate Professor and Director of the Technical Communication Program at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. | Headings, from Pearson | Headings from Technical Writing Essentials |

| Headings, from Grand Valley State University | “Subheadings: The Most Useful Technique in Tech Writing” from Tom Johnson at I’d Rather be Writing. |

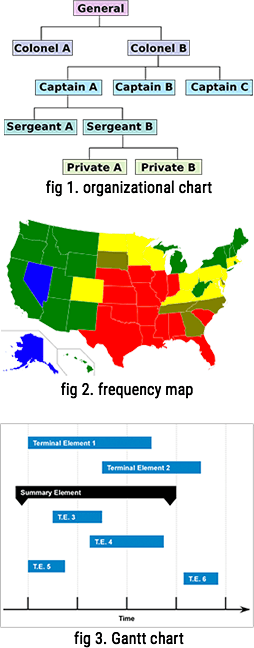

Access

When appropriate, visuals should accompany text to help convey complex ideas or data. This helps to make information understandable and accessible to audiences.

In professional documents, writers may decide to use lists, graphic organizers, tables, visual aids, charts, illustrations, or photographs to convey information that might be difficult to read, understand, or use in paragraph format.

| Graphic | Information Type & Uses |

| tables | organized or systematic display of data |

| maps | geographic information; data by location |

| bulleted lists | unordered or nonchronological information |

| numbered list | ordered, prioritized, or chronological information |

| pie chart | relationships between parts and the whole. |

| bar graph | simple comparisons; changes in quantity |

| line graph | trends or changes over time |

| flowchart | a process, often with shapes to represent (types of) activities |

| organization chart | organizational hierarchy; how an organization is set up |

| Gantt chart | project schedule with concurrant, overlapping, and linear phases |

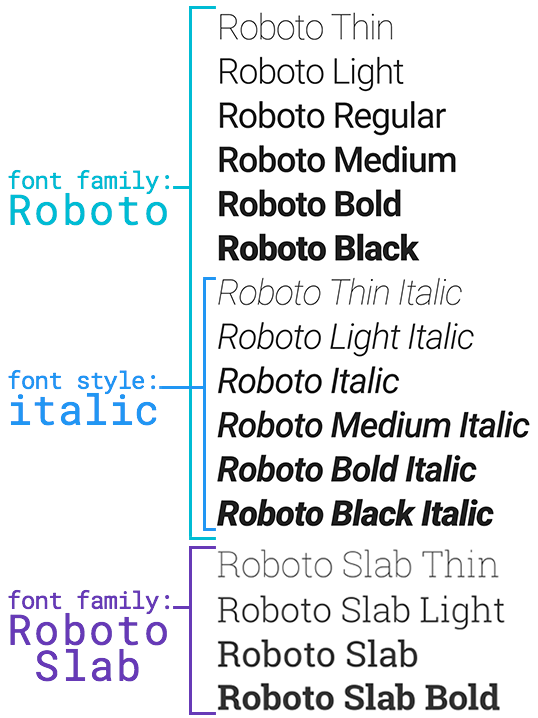

Typography

Type

Typeface can convey professionalism, illustrate contrast, and show hierarchical organization of information. In general, make sure body text is readable by using a 10-12 point common serif font such as Times New Roman (for print documents). Select a contrasting font for headings and vary type size and style for subheadings.

Avoid using more than two typefaces in routine business documents. Use size, style, and font variants (such as all caps, small caps, etc.) to indicate hierarchy and contrast. Above all else, make sure the text is readable.

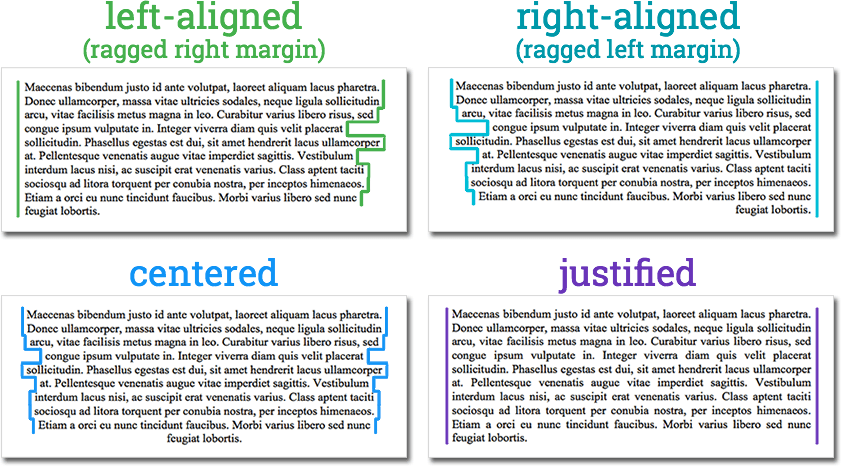

Alignment

left aligned text (or left justified text, or left alignment) aligns each line of text on the left margin (or an invisible left vertical rule). Left aligned (or left justified) left has a ragged right margin.

right aligned text (or right justified text, or right alignment) aligns each line of text on the right margin (or an invisible right vertical rule). Left aligned (or left justified) left has a ragged left margin.

center aligned text (or centered text) balances each line of text with equal length on both sides of the vertical center of the page or section. Centered text has both a ragged left and ragged right margin.

justified text (or full justified text) puts extra space between letters and/or words so blocks of text line up on both the left and right vertical rules.

Usually, the body or main text of a professional document should be left-aligned (or left-justified), leaving a “ragged” right margin.

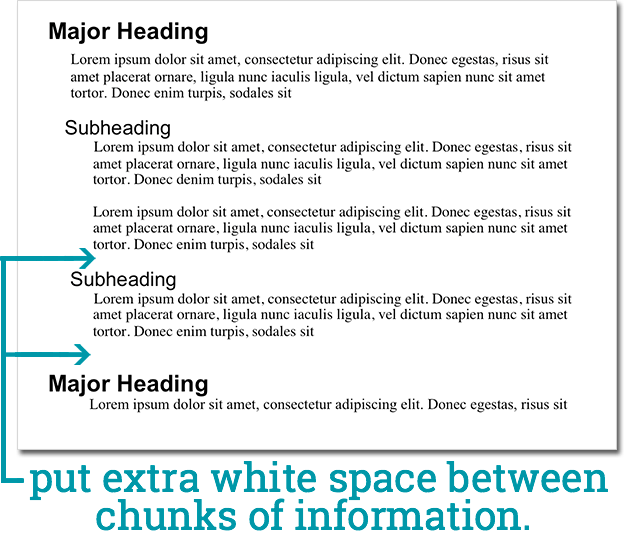

Space

The use of “white space” (or blank space) can promote the appearance of visual units, and in the same respect, can separate items that should not be grouped. Often times, document designers load up their pages with large text blocks, images, and other design elements with little or no blank space between them. This is burdensome to a reader and may cause her/him to skip information or skip over whole pages. Using white space effectively between visual elements that are related in some way gives the reader a sort of “break” between blocks of information, allowing them to process what they have read or experienced, and also making the page look less intimidating.

Using space is essential to “chunking”—a concept that works in both print and electronic writing.

Chunking is a method of presenting information which splits concepts into small pieces or “chunks” of information to make reading and understanding faster and easier. Chunking is especially useful for material presented on the web because readers tend to scan for specific information on a web page rather than read the page sequentially.

Chunked content usually contains:

- bulleted lists

- short subheadings

- short sentences with one or two ideas per sentence

- short paragraphs, even one-sentence paragraphs

- easily scannable text, with bolding of key phrases

- inline graphics to guide the eyes or illustrate points which would normally require more words

Large blocks of text with no visual groupings make information difficult and time consuming to understand.

|

Chunking information (as well as using headings and formatting for access) helps to make the document more readable, usable, and easier to understand.

|

Summary

To recap, ask these questions when using HATS:*

- Headings: Are there enough headings? Do they reflect a clear hierarchy of organization?

- Access: Is important information easy to find? Is the information easy to understand? Does the method of presentation enhance readability and clarity?

- Typography: Does the document use appropriate typefaces, size, styles, and alignment for both body text and headings?

- Space: Does the document have appropriate white space to make it inviting and easy to read?

A Final Note:

|

|

|

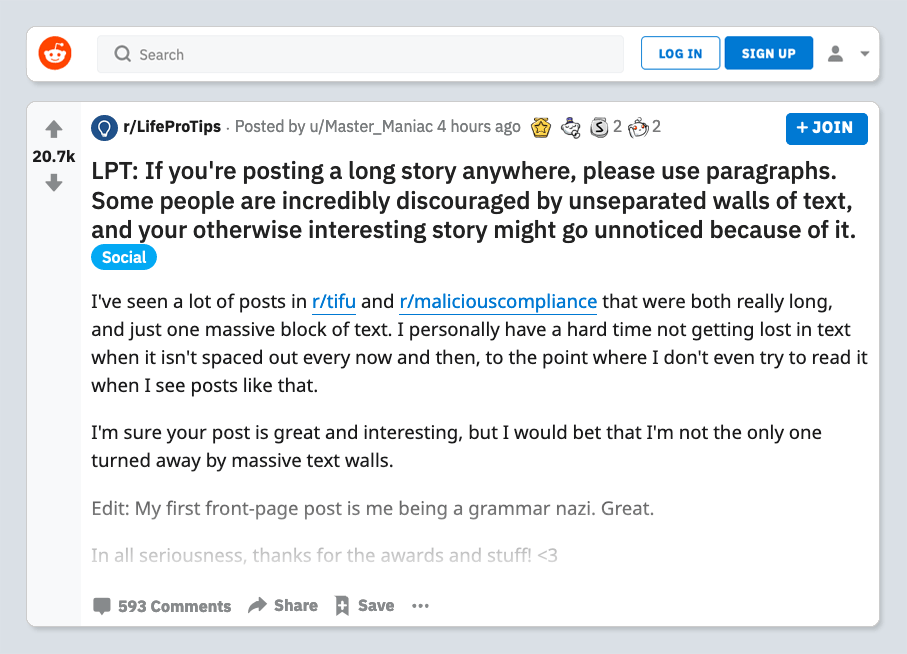

Nobody likes a wall of text.

|

|